| [1] |

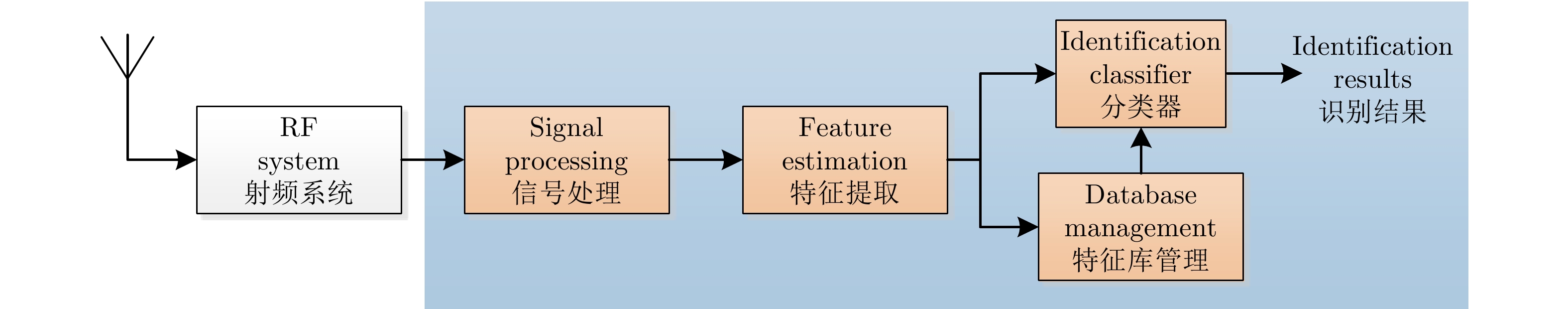

TALBOT K I, DULEY P R, and HYATT M H. Specific emitter identification and verification[J]. Technology Review Journal, 2003, : 113–133.

|

| [2] |

许丹. 辐射源指纹机理及识别方法研究[D]. [博士论文], 国防科学技术大学, 2008.

XU Dan. Research on mechanism and methodology of specific emitter identification[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], National University of Defense Technology, 2008.

|

| [3] |

徐书华. 基于信号指纹的通信辐射源个体识别技术研究[D]. [博士论文], 华中科技大学, 2007.

XU Shuhua. On the identification technique of individual transmitter based on signalprints[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], Huazhong University of Science and Technology, 2007.

|

| [4] |

ZI Xiaojun, XIE Dan, and YANG Jianbo. Emitter fingerprint feature extraction algorithm[J]. Ship Electronic Engineering, 2017, 37(3): 63–65, 121. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-9730.2017.03.016 |

| [5] |

LANGLEY L E. Specific emitter identification (SEI) and classical parameter fusion technology[C]. The WESCON’93, San Francisco, USA, 1993: 377–381.

|

| [6] |

贾永强. 通信辐射源个体识别技术研究[D]. [博士论文], 电子科技大学, 2017.

JIA Yongqiang. The research on communication emitters identification technology[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], School of Electronic Engineering, 2017.

|

| [7] |

DANEV B and CAPKUN S. Transient-based identification of wireless sensor nodes[C]. 2009 International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks, San Francisco, USA, 2009: 25–36.

|

| [8] |

YUAN Yingjun, HUANG Zhitao, WU Hao, et al. Specific emitter identification based on Hilbert-Huang transform-based time-frequency-energy distribution features[J]. IET Communications, 2014, 8(13): 2404–2412. doi: 10.1049/iet-com.2013.0865 |

| [9] |

SATIJA U, TRIVEDI N, BISWAL G, et al. Specific emitter identification based on variational mode decomposition and spectral features in single hop and relaying scenarios[J]. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2019, 14(3): 581–591. doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2018.2855665 |

| [10] |

GUO Shanzeng, WHITE R E, and LOW M. A comparison study of radar emitter identification based on signal transients[C]. 2018 IEEE Radar Conference (RadarConf18), Oklahoma City, USA, 2018: 0286–0291.

|

| [11] |

DAVIES C L and HOLLANDS P. Automatic processing for ESM[J]. IEE Proceedings F - Communications, Radar and Signal Processing, 1982, 129(3): 164–171. doi: 10.1049/ip-f-1.1982.0025 |

| [12] |

ABRAHAMZADEH A, SEYEDIN S A, and DEHGHAN M. Digital-signal-type identification using an efficient identifier[J].EURASIP Journal on Advances in Signal Processing, 2007, 2007: 63.

|

| [13] |

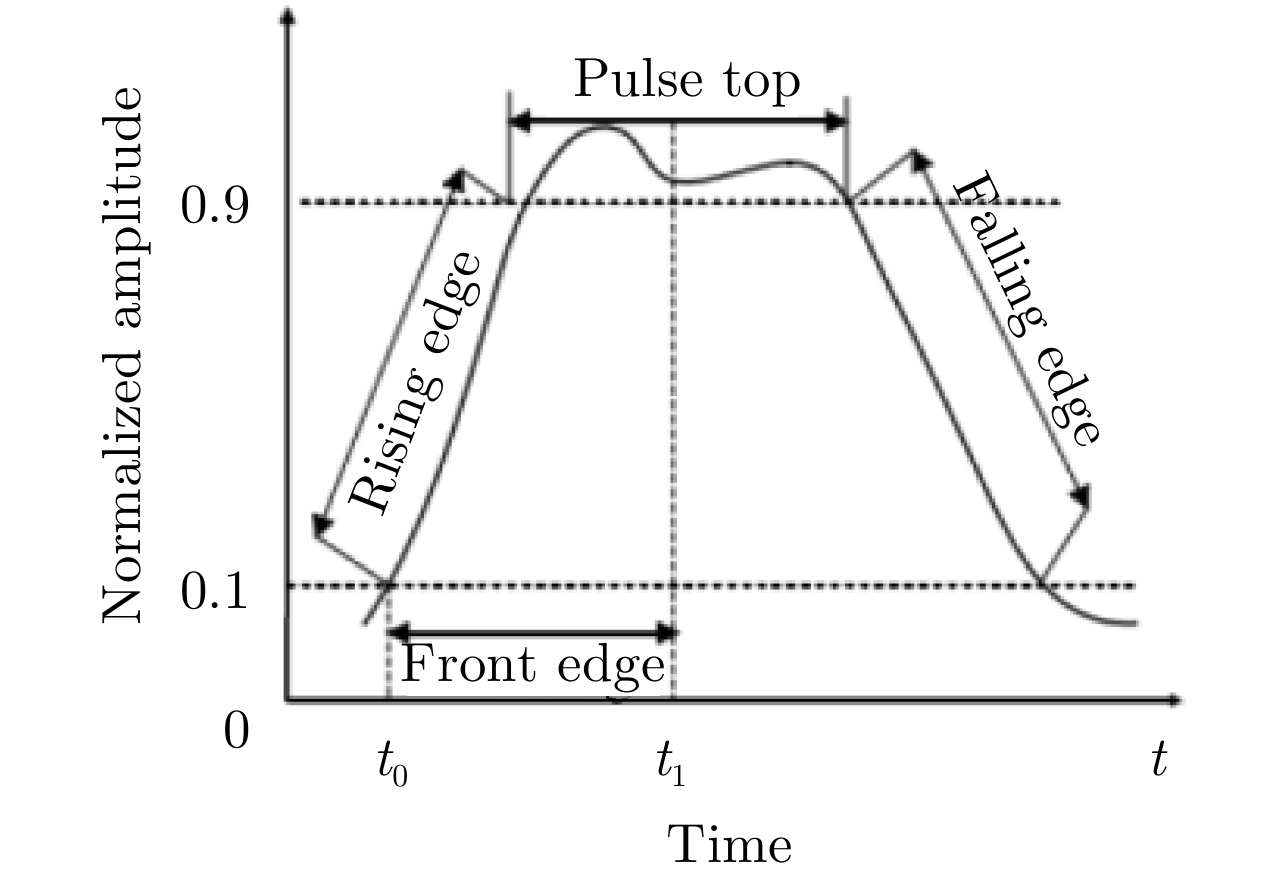

WANG Hongwei, ZHAO Guoqing, and WANG Yujun. A specific emitter identification method based on front edge waveform of radar signal envelop[J]. Aerospace Electronic Warfare, 2009, 25(2): 35–38. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-2421.2009.02.011 |

| [14] |

刘旭, 罗鹏飞, 李纲. 基于拟合角特征及SVM的雷达辐射源个体识别[J]. 计算机工程与应用, 2011, 47(8S): 281–284.

LIU Xu, LUO Pengfei, and LI Gang. Radar emitter individual identification based on fitting angle features and SVM[J]. Computer Engineering and Applications, 2011, 47(8S): 281–284.

|

| [15] |

XU Shuhua, XU Lina, XU Zhengguang, et al. Individual radio transmitter identification based on spurious modulation characteristics of signal envelop[C]. 2008 IEEE Military Communications Conference, San Diego, USA, 2008: 1–5.

|

| [16] |

ZHANG Guozhu, HUANG Kesheng, JIANG Weili, et al. Emitter feature extract method based on signal envelope[J]. Systems Engineering and Electronics, 2006, 28(6): 795–797, 936. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1001-506X.2006.06.002 |

| [17] |

REHMAN S U, SOWERBY K, and COGHILL C. RF fingerprint extraction from the energy envelope of an instantaneous transient signal[C]. 2012 Australian Communications Theory Workshop (AusCTW), Wellington, New Zealand, 2012: 90–95.

|

| [18] |

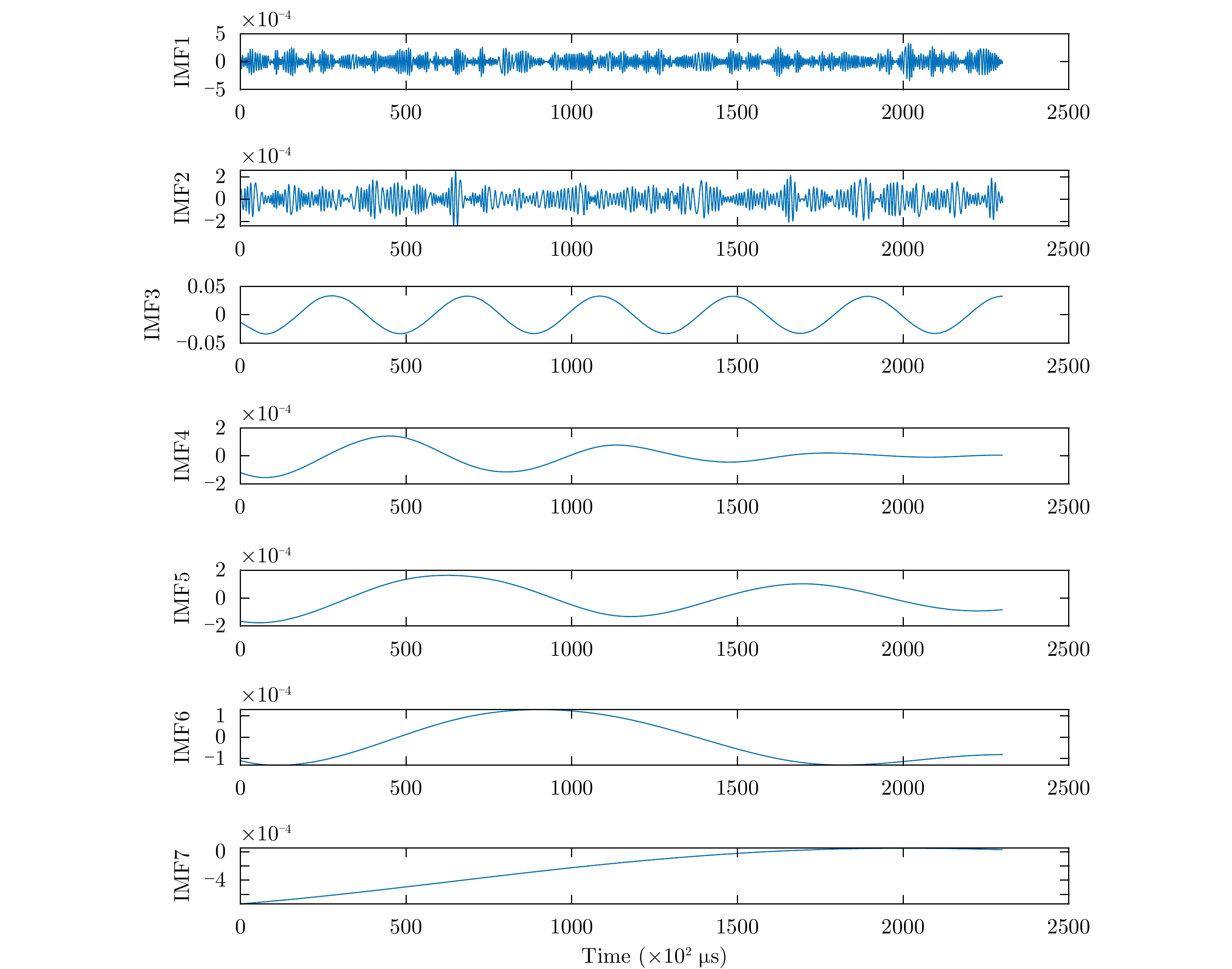

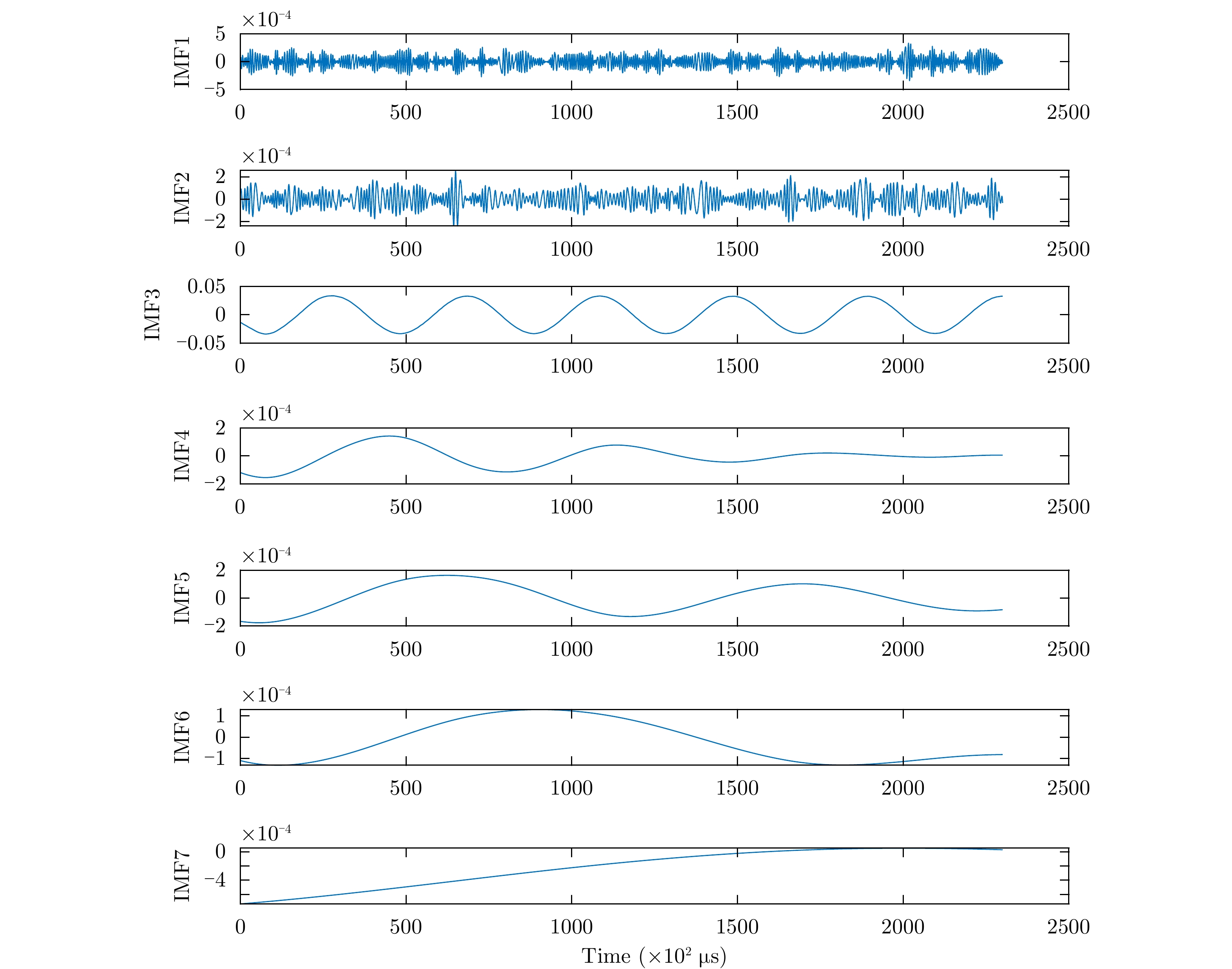

WU Longwen, ZHAO Yaqin, FENG Mengfei, et al. Specific emitter identification using IMF-DNA with a joint feature selection algorithm[J]. Electronics, 2019, 8(9): 934. doi: 10.3390/electronics8090934 |

| [19] |

FENG Zhipeng, ZHANG Dong, and ZUO M J. Adaptive mode decomposition methods and their applications in signal analysis for machinery fault diagnosis: A review with examples[J]. IEEE Access, 2017, 5: 24301–24331. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2766232 |

| [20] |

HALL J, BARBEAU M, and KRANAKIS E. Enhancing intrusion detection in wireless networks using radio frequency fingerprinting[C]. Communications, Internet, and Information Technology, St. Thomas, US Virgin Islands, USA, 2004: 201–206.

|

| [21] |

HALL J, BARBEAU M, and KRANAKIS E. Detecting rogue devices in bluetooth networks using radio frequency fingerprinting[C]. The 3rd IASTED International Conference on Communications and Computer Networks, Lima, Peru, 2006: 108–113.

|

| [22] |

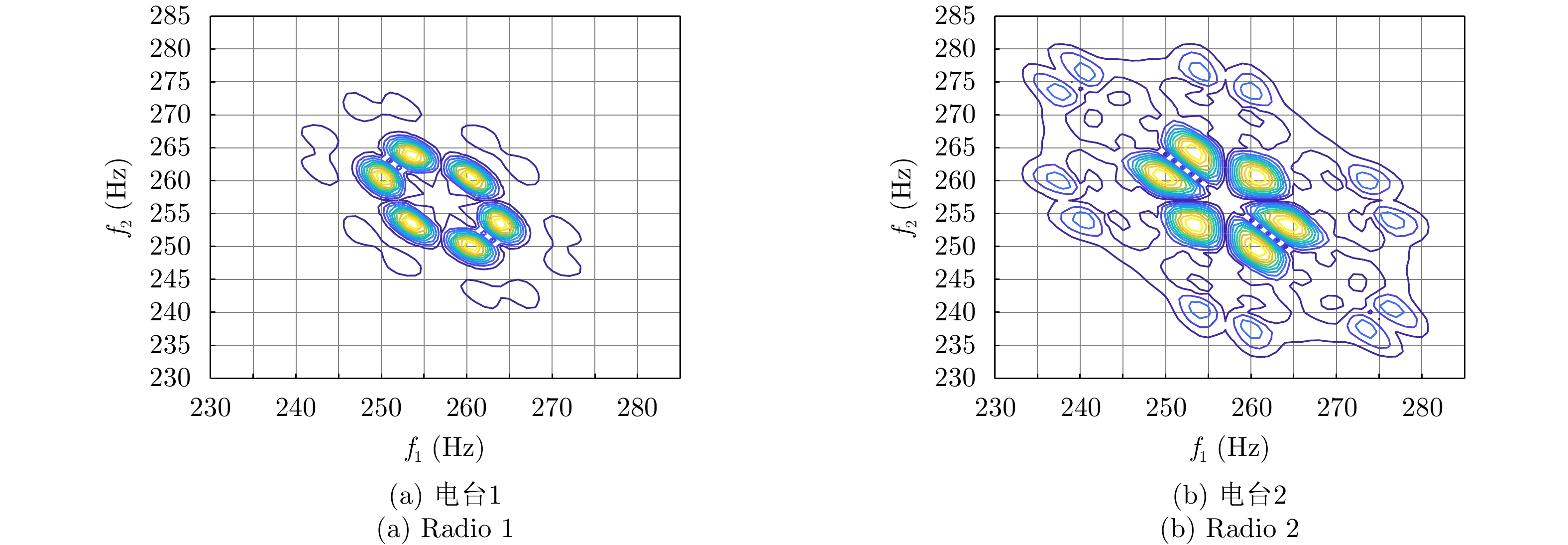

HUANG Yuanling and ZHENG Hui. FSK radio fingerprints extraction based on distortions of instantaneous frequency[J]. Telecommunication Engineering, 2013, 53(7): 868–872. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-893x.2013.07.009 |

| [23] |

PADILLA P, PADILLA J L, and VALENZUELA-VALDÉS J F. Radiofrequency identification of wireless devices based on RF fingerprinting[J]. Electronics Letters, 2013, 49(22): 1409–1410. doi: 10.1049/el.2013.2759 |

| [24] |

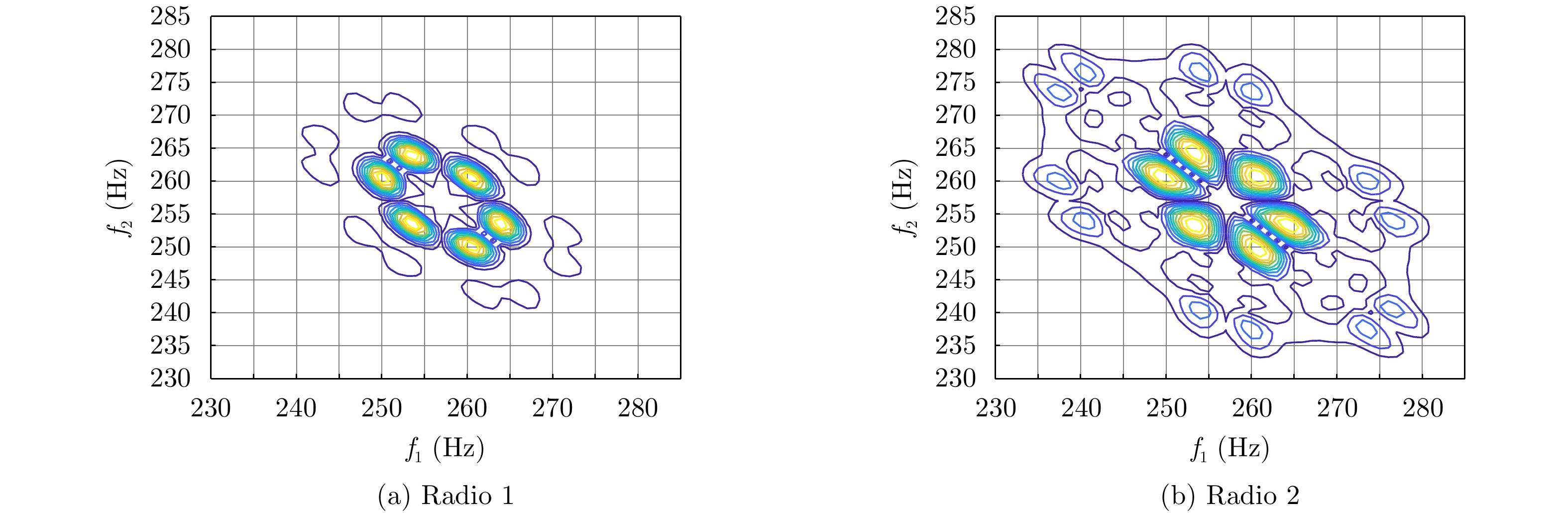

BRIK V, BANERJEE S, GRUTESER M, et al. Wireless device identification with radiometric signatures[C]. The 14th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, MOBICOM 2008, San Francisco, USA, 2008: 116–127.

|

| [25] |

WANG Wei, LI Shixian, and WANG Xin. A communication SEI approach based on constellation diagram[J]. Journal of Hunan City University: Natural Science, 2017, 26(5): 51–55. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7304.2017.05.0011 |

| [26] |

CHENG Hanwen and WU Le’nan. Classification of modulation techniques using constellation shape and similarity measure[J]. Journal of Applied Sciences-Electronics and Information Engineering, 2008, 26(2): 111–116. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.0255-8297.2008.02.001 |

| [27] |

RU Xiaohu, LIU Zheng, HUANG Zhitao, et al. Evaluation of unintentional modulation for pulse compression signals based on spectrum asymmetry[J]. IET Radar, Sonar& Navigation, 2017, 11(4): 656–663. doi: 10.1049/iet-rsn.2016.0248 |

| [28] |

YE Wenqiang and YU Zhifu. Signal recognition method based on joint time-frequency radiant source[J]. Electronic Information Warfare Technology, 2018, 33(5): 16–19, 50. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2230.2018.05.004 |

| [29] |

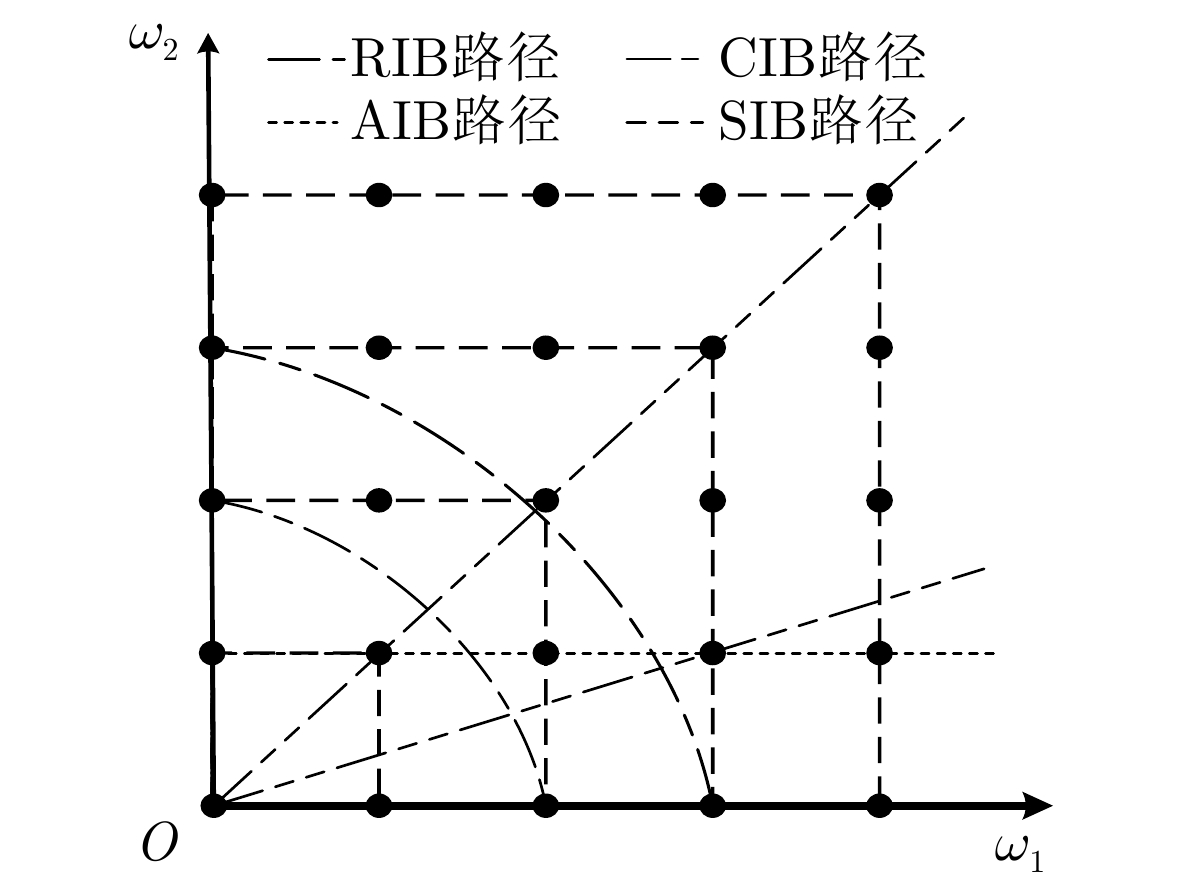

FLAMANT J, LE BIHAN N, and CHAINAIS P. Time-frequency analysis of bivariate signals[J]. Applied and Computational Harmonic Analysis, 2019, 46(2): 351–383. doi: 10.1016/j.acha.2017.05.007 |

| [30] |

BERTONCINI C, RUDD K, NOUSAIN B, et al. Wavelet fingerprinting of Radio-Frequency IDentification (RFID) tags[J]. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics, 2012, 59(12): 4843–4850. doi: 10.1109/TIE.2011.2179276 |

| [31] |

HIPPENSTIEL R D. Wavelet based approach to transmitter identification[R]. NPS-EC-95-014, 1995.

|

| [32] |

GAO Jingpeng, KONG Weiyu, LIU Jiaqi, et al. Research on emitter modulation recognition of the adaptive PCA based on time-frequency analysis[J]. Applied Science and Technology, 2018, 45(5): 33–37. doi: 10.11991/yykj.201712013 |

| [33] |

XIE Zhenhua, XU Luping, NI Guangren, et al. A new feature vector using selected line spectra for pulsar signal bispectrum characteristic analysis and recognition[J]. Chinese Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2007, 7(4): 565–571.

|

| [34] |

CAI Zhongwei and LI Jiandong. Study of transmitter individual identification based on bispectra[J]. Journal on Communications, 2007, 28(2): 75–79. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1000-436X.2007.02.012 |

| [35] |

WANG Huanhuan and ZHANG Tao. Extraction algorithm of communication signal characteristics based on improved bispectra and time-domain Analysis[J]. Journal of Signal Processing, 2017, 33(6): 864–871. doi: 10.16798/j.issn.1003-0530.2017.06.012 |

| [36] |

YANG Ju, LU Xuanmin, and ZHOU Yajian. Transmitter individual identification based on polyspectra and support Vector Machine[J]. Computer Simulation, 2010, 27(11): 349–353. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9348.2010.11.088 |

| [37] |

GONG Yong, HU Guyu, and PAN Zhisong. Radio transmitter identification based on bispectra with tensor representation[C]. 2010 2nd International Conference on Computer Engineering and Technology, Chengdu, China, 2010: V3-294–V3-298.

|

| [38] |

刘婷. 基于循环平稳分析的雷达辐射源特征提取与融合识别[D]. [硕士论文], 西安电子科技大学, 2009.

LIU Ting. Feature extraction and fusion recognition of radar radiation source based on cyclic stationary analysis[D]. [Master dissertation], Xidian University, 2009.

|

| [39] |

CHEN Zhiwei, XU Zhijun, WANG Jinming, et al. Emitter identification method based on cyclic spectrum density slice[J]. Journal of Data Acquisition& Processing, 2013, 28(3): 284–288. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-9037.2013.03.005 |

| [40] |

WANG Huanhuan, ZHANG Tao, and MENG Fanyu. Specific emitter identification based on time-frequency domain characteristic[J]. Journal of Information Engineering University, 2018, 19(1): 23–29. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0673.2018.01.006 |

| [41] |

王丽. 低频辐射源细微特征分析[D]. [硕士论文], 南京航空航天大学, 2014.

WANG Li. Analysis of subtle characteristics of low-frequency radiation[D]. [Master dissertation], Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, 2014.

|

| [42] |

桂云川, 杨俊安, 吕季杰, 等. 基于经验模态分解的通信辐射源分形特征提取算法[J]. 探测与控制学报, 2016, 38(1): 104–108.

GUI Yunchuan, YANG Jun’an, LV Jijie, et al. A fractal feature extraction algorithm based on empirical mode decomposition[J]. Journal of Detection&Control, 2016, 38(1): 104–108.

|

| [43] |

ZHANG Jingwen, WANG Fanggang, DOBRE O A, et al. Specific emitter identification via Hilbert-Huang transform in single-hop and relaying scenarios[J]. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2016, 11(6): 1192–1205.

|

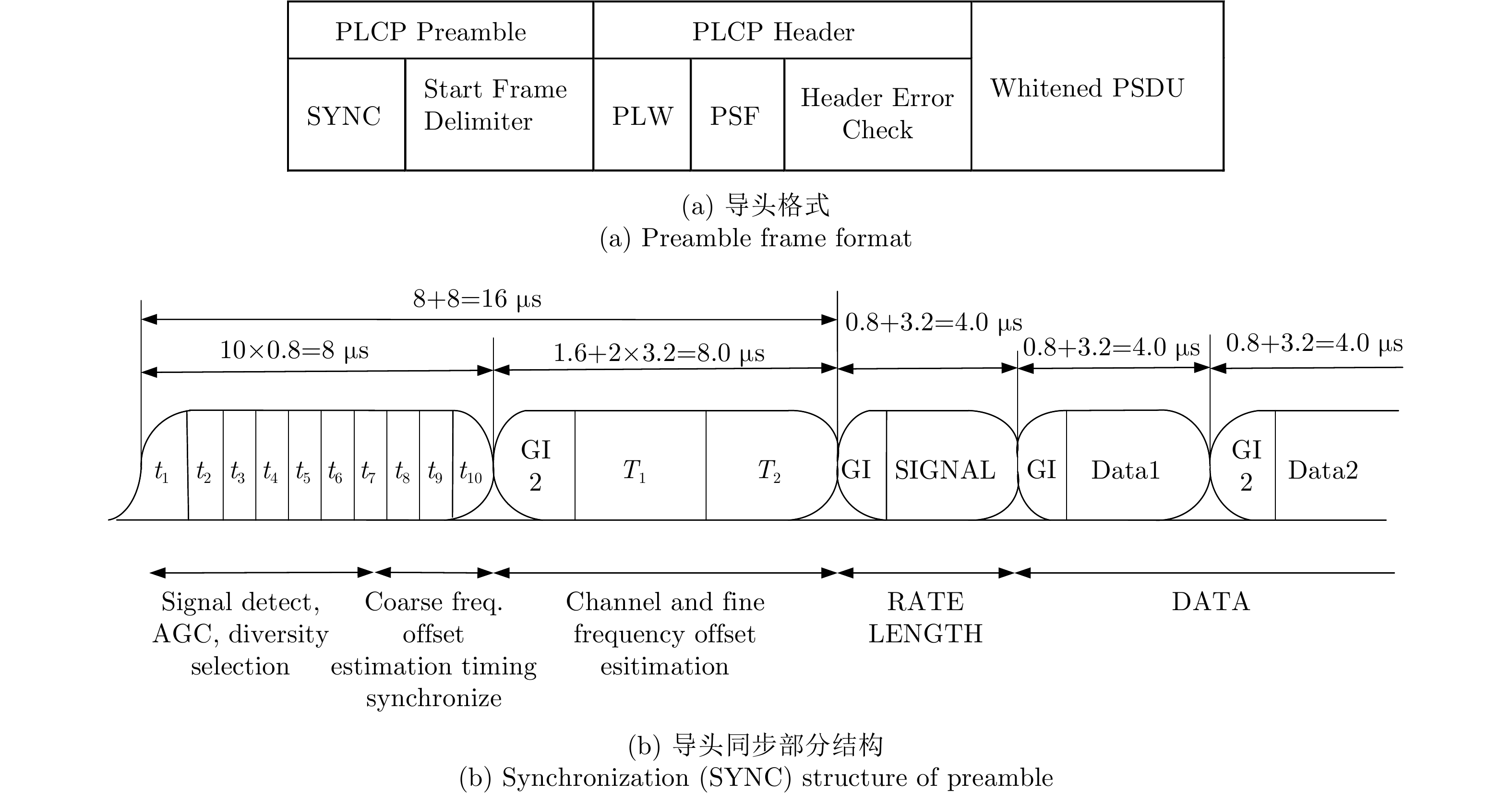

| [44] |

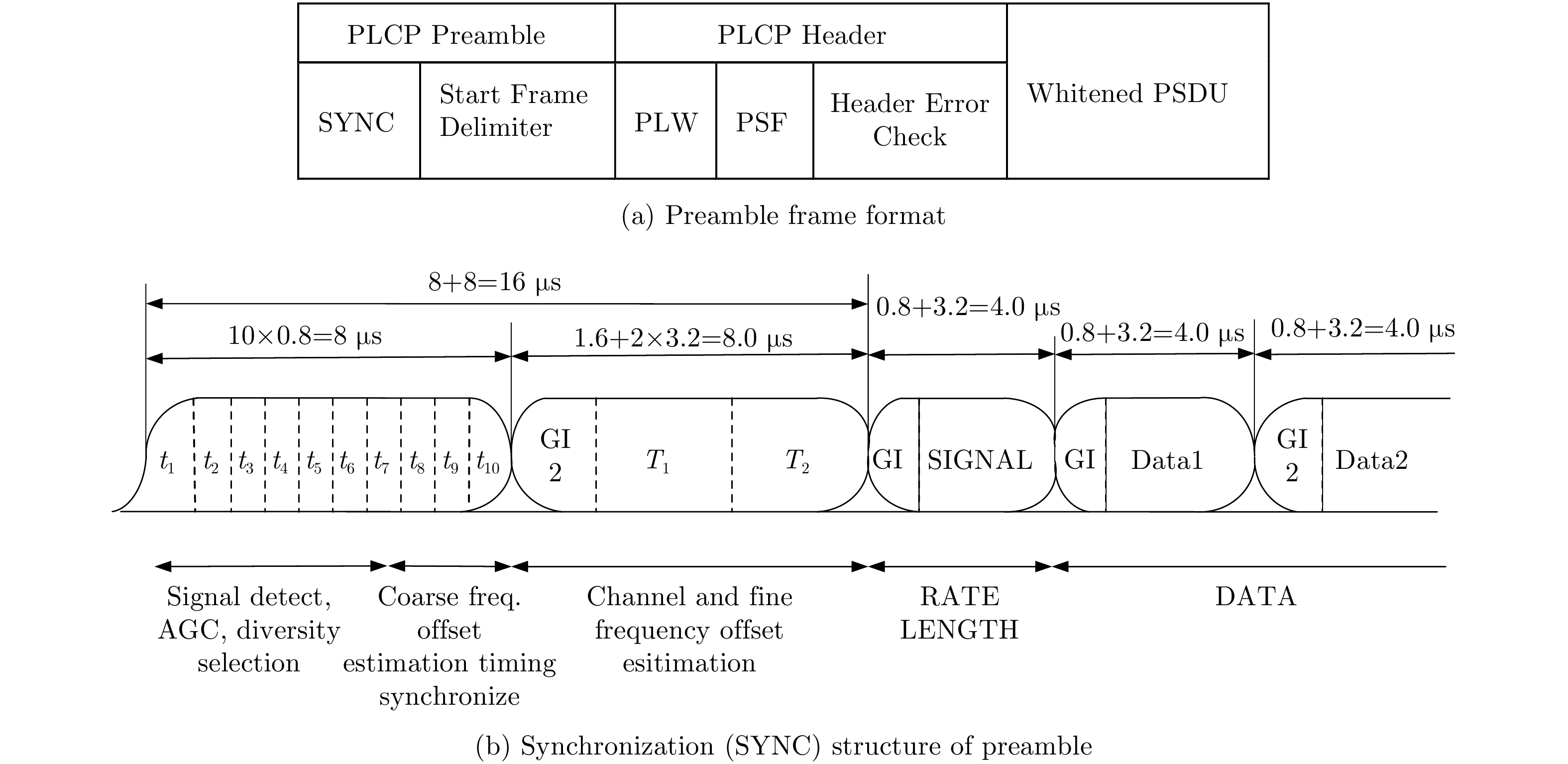

YUAN H L and HU A Q. Preamble-based detection of Wi-Fi transmitter RF fingerprints[J]. Electronics Letters, 2010, 46(16): 1165–1167. doi: 10.1049/el.2010.1220 |

| [45] |

WU Qingyang, FERES C, KUZMENKO D, et al. Deep learning based RF fingerprinting for device identification and wireless security[J]. Electronics Letters, 2018, 54(24): 1405–1407.

|

| [46] |

YE Haohuan, LIU Zheng, and JIANG Wenli. A comparison of unintentional modulation on pulse features with the consideration of Doppler effect[J]. Journal of Electronics& Information Technology, 2012, 34(11): 118–123. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1146.2012.00400 |

| [47] |

PU Yunwei, JIN Weidong, ZHU Ming, et al. Extracting the main ridge slice characteristics of ambiguity function for radar emitter signals[J]. Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves, 2008, 27(2): 133–137. doi: 10.3321/j.issn:1001-9014.2008.02.012 |

| [48] |

LI Lin and JI Hongbing. Specific emitter identification based on ambiguity function[J]. Journal of Electronics& Information Technology, 2009, 31(11): 2546–2551. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1146.2008.01406 |

| [49] |

王磊, 姬红兵, 史亚. 基于模糊函数特征优化的雷达辐射源个体识别[J]. 红外与毫米波学报, 2011, 30(1): 74–79.

WANG Lei, JI Hongbing, and SHI Ya. Feature optimization of ambiguity function for radar emitter recognition[J]. Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves, 2011, 30(1): 74–79.

|

| [50] |

王磊, 姬红兵, 李林. 基于模糊函数零点切片特征优化的辐射源个体识别[J]. 西安电子科技大学学报: 自然科学版, 2010, 37(2): 285–289, 304.

WANG Lei, JI Hongbing, and LI Lin. Specific emitter recognition based on feature optimization of ambiguity function zero-slice[J]. Journal of Xidian University, 2010, 37(2): 285–289, 304.

|

| [51] |

WANG Lei, JI Hongbing, and SHI Ya. Moving radar emitter recognition based on representative-cut feature of ambiguity function[J]. Systems Engineering and Electronics, 2010, 32(8): 1630–1634. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-506X.2010.08.16 |

| [52] |

HUANG N E, SHEN Zheng, LONG S R, et al. The empirical mode decomposition and the Hilbert spectrum for nonlinear and non-stationary time series analysis[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society A:Mathematical,Physical and Engineering Sciences, 1998, 454(1971): 903–995.

|

| [53] |

SONG Chunyun, XU Jianmin, and ZHAN Yi. A method for specific emitter identification based on empirical mode decomposition[C]. 2010 IEEE International Conference on Wireless Communications, Networking and Information Security, Beijing, China, 2010: 54–57.

|

| [54] |

HA Zhang, LIU Xiangde, CAI Qiang, et al. Study of specific emitter identification for ATC transponder[J]. Electronic Information Warfare Technology, 2012, 27(3): 1–5, 27. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-2230.2012.03.001 |

| [55] |

LIANG Jianghai, HUANG Zhitao, YUAN Yingjun, et al. A method based on empirical mode decomposition for identifying transmitter individuals[J]. Journal of CAEIT, 2013, 8(4): 393–397, 417. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5692.2013.04.013 |

| [56] |

FREI M G and OSORIO I. Intrinsic time-scale decomposition: time-frequency-energy analysis and real-time filtering of non-stationary signals[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 2007, 463(2078): 321–342. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2006.1761 |

| [57] |

LI Xuecheng, DUAN Tiandong, XU Wenyan, et al. ITD-based identification of signal fine features[J]. Journal of Information Engineering University, 2014, 15(5): 570–575. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-0673.2014.05.010 |

| [58] |

GUI Yunchuan, YANG Jun’an, and LYU Jijie. Feature extraction algorithm based on intrinsic time-scale decomposition model for communication transmitter[J]. Application Research of Computers, 2017, 34(4): 1172–1175. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-3695.2017.04.049 |

| [59] |

REN Dongfang, ZHANG Tao, and HAN Jie. Approach of specific communication emitter identification combining ITD and nonlinear analysis[J]. Journal of Signal Processing, 2018, 34(3): 331–339. doi: 10.16798/j.issn.1003-0530.2018.03.010 |

| [60] |

REN Dongfang, ZHANG Tao, HAN Jie, et al. Specific emitter identification based on ITD and texture analysis[J]. Journal on Communications, 2017, 38(12): 160–168. doi: 10.11959/j.issn.1000-436x.2017299 |

| [61] |

MARTIS R J, ACHARYA U R, TAN J H, et al. Application of Intrinsic Time-scale Decomposition (ITD) to EEG signals for automated seizure prediction[J]. International Journal of Neural Systems, 2013, 23(5): 1350023. doi: 10.1142/S0129065713500238 |

| [62] |

AN Xueli, JIANG Dongxiang, CHEN Jie, et al. Application of the intrinsic time-scale decomposition method to fault diagnosis of wind turbine bearing[J]. Journal of Vibration and Control, 2012, 18(2): 240–245. doi: 10.1177/1077546311403185 |

| [63] |

XU Yonggang, XIE Zhicong, CUI Linli, et al. The feature extraction method of gear magnetic memory signal[J]. Advanced Materials Research, 2013, 819: 206–211. doi: 10.4028/www.scientific.net/AMR.819.206 |

| [64] |

DRAGOMIRETSKIY K and ZOSSO D. Variational mode decomposition[J]. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 2014, 62(3): 531–544. doi: 10.1109/TSP.2013.2288675 |

| [65] |

陈尚, 郑翔. 基于VMD能量熵与支持向量机的断路器机械故障诊断方法研究[J]. 黑龙江电力, 2019, 41(1): 60–63.

CHEN Shang and ZHENG Xiang. Research on mechanical fault diagnosis method of circuit breaker based on VMD energy entropy and support vector machine[J]. Heilongjiang Electric Power, 2019, 41(1): 60–63.

|

| [66] |

孟庆芳. 非线性动力系统时间序列分析方法及其应用研究[D]. [博士论文], 山东大学, 2008.

MENG Qingfang. Nonlinear dynamical time series analysis methods and its application[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], Shandong University, 2008.

|

| [67] |

CARROLL T L. A nonlinear dynamics method for signal identification[J]. Chaos: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, 2007, 17(2): 023109. doi: 10.1063/1.2722870 |

| [68] |

袁英俊. 通信辐射源个体识别关键技术研究[D]. [博士论文], 长沙: 国防科技大学, 2014.

YUAN Yingjun. Research on key technology of communication specific emitter identification[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], National University of Defense Technology, 2014.

|

| [69] |

朱胜利. 混沌信号处理在辐射源个体识中的应用研究[D]. [博士论文], 电子科技大学, 2018.

ZHU Shengli. Research on applications of chaotic signal processing in specific emitter identification[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], School of Information and Communication, 2018.

|

| [70] |

BIHL T J, BAUER K W, and TEMPLE M A. Feature selection for RF fingerprinting with multiple discriminant analysis and using ZigBee device emissions[J]. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 2016, 11(8): 1862–1874. doi: 10.1109/TIFS.2016.2561902 |

| [71] |

ZHU Shengli and GAN Lu. Specific emitter identification based on visibility graph entropy[J]. Chinese Physics Letters, 2018, 35(3): 030501.

|

| [72] |

XU Dan, XU Haiyuan, LU Qizhong, et al. A specific emitter identification method based on self-excitation oscillator model[J]. Signal Processing, 2008, 24(1): 122–126. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1003-0530.2008.01.029 |

| [73] |

徐志军, 陈志伟, 王金明, 等. 基于功放特性的辐射源识别的改进方法[J]. 南京邮电大学学报: 自然科学版, 2013, 33(6): 54–58.

XU Zhijun, CHEN Zhiwei, WANG Jinming, et al. An improved method for emitter identification based on character of power amplifier[J]. Journal of Nanjing University of Posts and Telecommunications:Natural Science, 2013, 33(6): 54–58.

|

| [74] |

HUANG Yuanling and ZHENG Hui. Emitter fingerprint feature extraction method based on characteristics of phase noise[J]. Computer Simulation, 2013, 30(9): 182–185. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1006-9348.2013.09.042 |

| [75] |

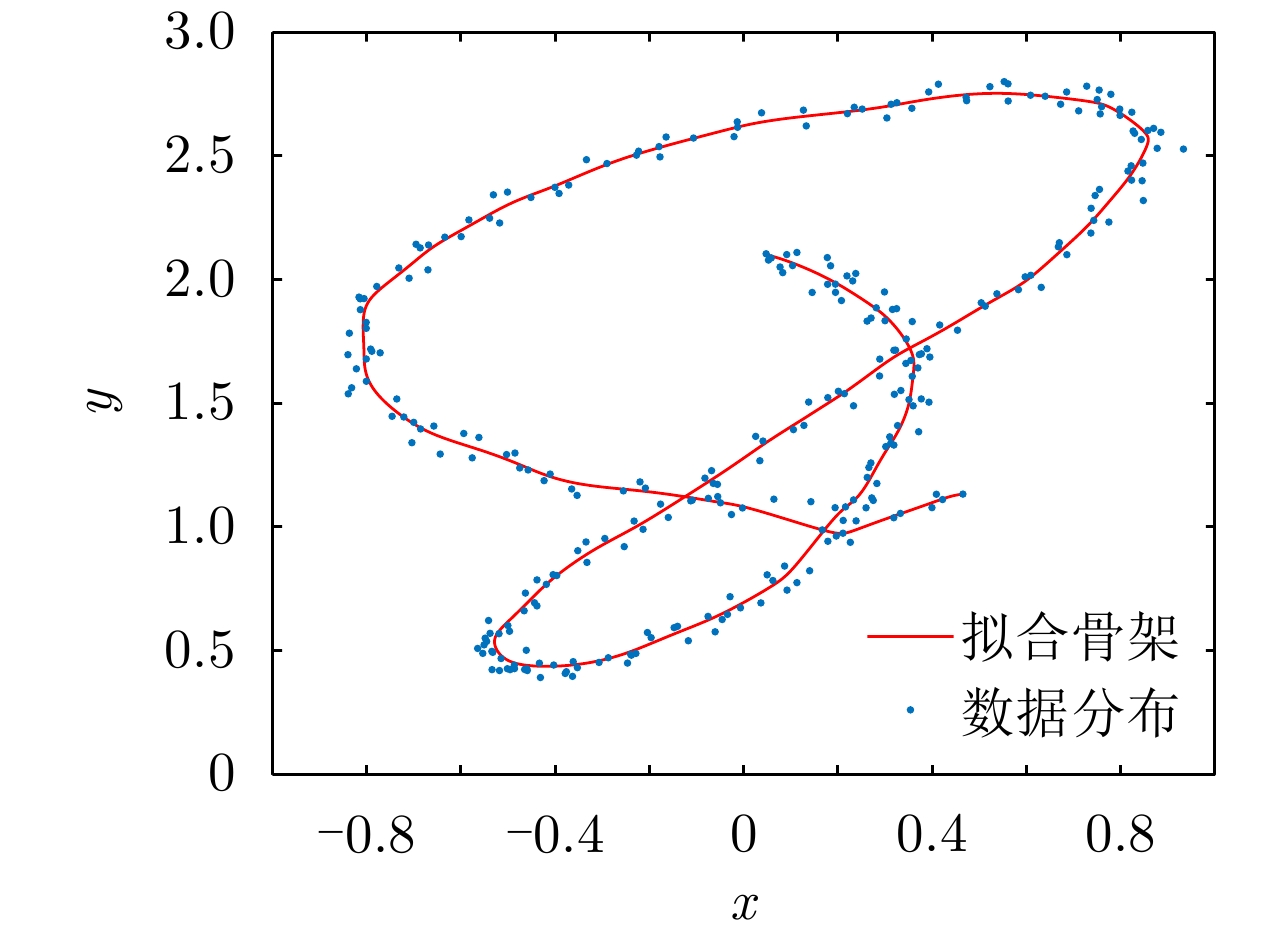

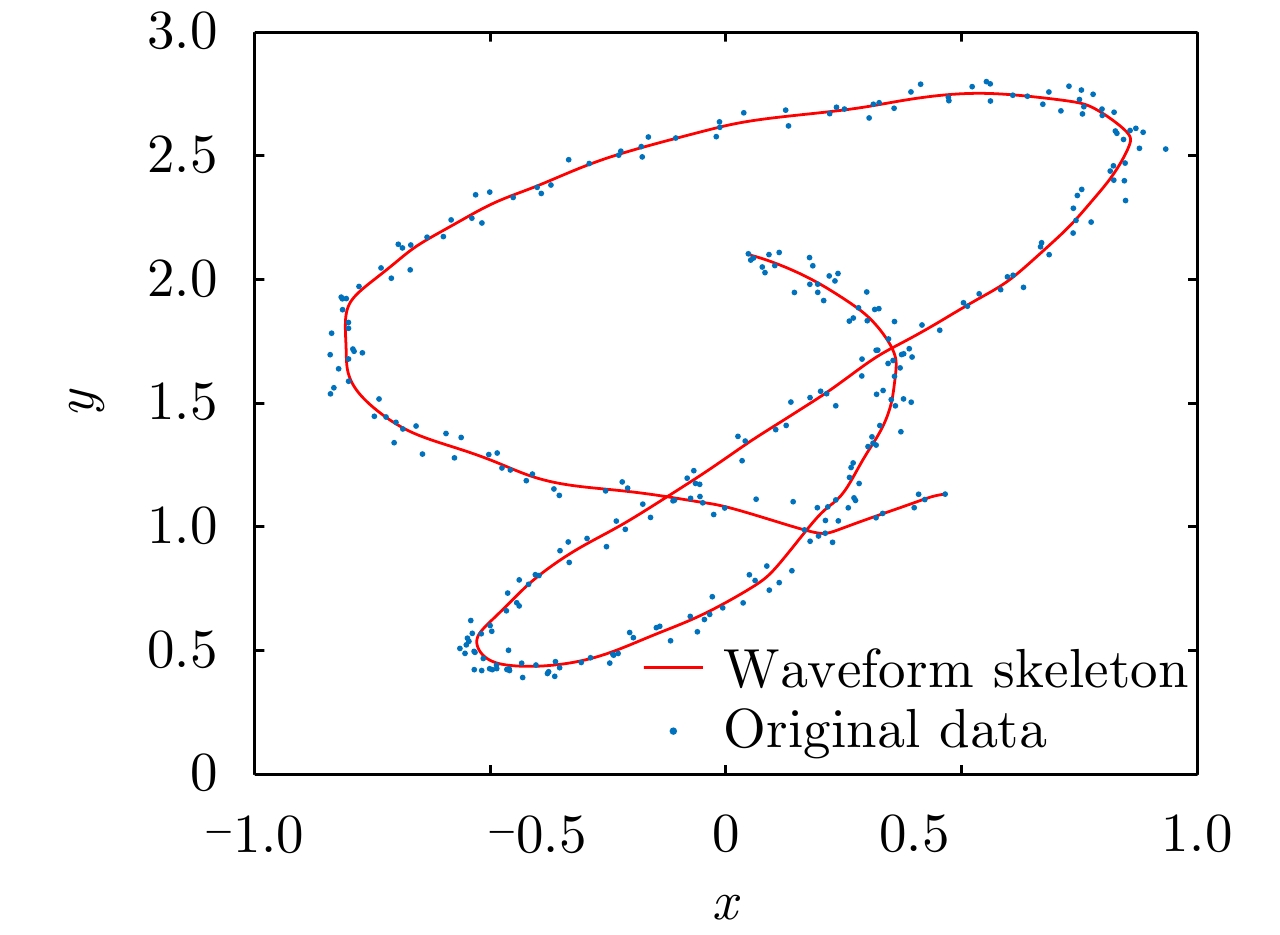

马驰, 张红云, 苗夺谦. 改进的主曲线算法在指纹骨架提取中的应用[J]. 计算机工程与应用, 2010, 46(16): 170–173.

MA Chi, ZHANG Hongyun, and MIAO Duoqian. Improvement of principal curves algorithm and its application in finger-print skeleton extraction[J]. Computer Engineering and Applications, 2010, 46(16): 170–173.

|

| [76] |

WANG Huanhuan and ZHANG Tao. Higher-order spectrum skeleton application to signal fine character identification[J]. Computer Applications and Software, 2017, 34(8): 179–184. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-386x.2017.08.032 |

| [77] |

LI Xuecheng, DUAN Tiandong, XU Wenyan, et al. Identifying imperceptible feature of signals based on soft K-segments algorithm for principal curves[J]. Computer Applications and Software, 2015, 32(5): 198–202. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1000-386x.2015.05.048 |

| [78] |

官建平. 基于双谱的辐射源个体识别技术[D]. [硕士论文], 西安电子科技大学, 2014.

GUAN Jianping. Study of individual transmitter identification based on bispectrum[D]. [Master dissertation], Xidian University, 2014.

|

| [79] |

唐智灵, 杨小牛, 李建东. 调制无线电信号的分形特征研究[J]. 物理学报, 2011, 60(5): 550–556.

TANG Zhiling, YANG Xiaoniu, and LI Jiandong. Study on fractal features of modulated radio signal[J]. Acta Physica Sinica, 2011, 60(5): 550–556.

|

| [80] |

WU Longwen, ZHAO Yaqin, WANG Zhao, et al. Specific emitter identification using fractal features based on box-counting dimension and variance dimension[C]. 2017 IEEE International Symposium on Signal Processing and Information Technology (ISSPIT), Bilbao, Spain, 2017: 226–231.

|

| [81] |

桂云川, 杨俊安, 万俊. 基于双谱特征融合的通信辐射源识别算法[J]. 探测与控制学报, 2016, 38(5): 91–95.

GUI Yunchuan, YANG Jun’an, and WAN Jun. A transmitter recognition algorithm based on dual spectrum feature fusion[J]. Journal of Detection&Control, 2016, 38(5): 91–95.

|

| [82] |

HUANG Guangquan, YUAN Yingjun, WANG Xiang, et al. Specific emitter identification based on nonlinear dynamical characteristics[J]. Canadian Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering, 2016, 39(1): 34–41. doi: 10.1109/CJECE.2015.2496143 |

| [83] |

XU Yulong, WANG Jinming, XU Zhijun, et al. Fingerprint feature extraction method for emitters based on wavelet entropy[J]. Journal of Data Acquisition and Processing, 2014, 29(4): 631–635. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-9037.2014.04.022 |

| [84] |

TANG Zhe and LEI Yingke. Method of individual communication transmitter identification based on maximum correntropy[J]. Journal on Communications, 2016, 37(12): 175–179. doi: 10.11959/j.issn.1000-436x.2016283 |

| [85] |

SAHMEL P H, REED J H, and SPOONER C M. Eigenspace approach to specific emitter identification[J]. Frequenz, 2010, 64(11/12): 229–235.

|

| [86] |

王磊. 雷达辐射源个体识别的方法研究[D]. [博士论文], 西安电子科技大学, 2011.

WANG Lei. On methods for specific radar emitter identification[D]. [Ph.D. dissertation], Xidian University, 2011.

|

| [87] |

XU Shuhua, HUANG Benxiong, XU Lina, et al. Radio transmitter classification using a new method of stray features analysis combined with PCA[C]. Military Communications Conference, Orlando, USA, 2007: 1–5.

|

| [88] |

YE Wenqiang and PENG Cong. Recognition algorithm of emitter signals based on PCA+CNN[C]. 2018 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference, Chongqing, China, 2018: 2410–2414.

|

| [89] |

DING Lida, WANG Shilian, WANG Fanggang, et al. Specific emitter identification via convolutional neural networks[J]. IEEE Communications Letters, 2018, 22(12): 2591–2594.

|

| [90] |

BITAR N, MUHAMMAD S, and REFAI H H. Wireless technology identification using deep convolutional neural networks[C]. 2017 IEEE 28th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications, Montreal, Canada, 2017: 1–6.

|

| [91] |

WONG L J, HEADLEY W C, ANDREWS S, et al. Clustering learned CNN features from raw I/Q data for emitter identification[C]. MILCOM 2018-2018 IEEE Military Communications Conference (MILCOM), Los Angeles, USA, 2018: 26–33.

|

| [92] |

RIYAZ S, SANKHE K, IOANNIDIS S, et al. Deep learning convolutional neural networks for radio identification[J]. IEEE Communications Magazine, 2018, 56(9): 146–152. doi: 10.1109/MCOM.2018.1800153 |

| [93] |

YOUSSEF K, BOUCHARD L, HAIGH K, et al. Machine learning approach to RF transmitter identification[J]. IEEE Journal of Radio Frequency Identification, 2018, 2(4): 197–205. doi: 10.1109/JRFID.2018.2880457 |

| [94] |

MCGINTHY J M, WONG L J, and MICHAELS A J. Groundwork for neural network-based specific emitter identification authentication for IoT[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2019, 6(4): 6429–6440. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2019.2908759 |

| [95] |

WU Xiaopo, SHI Yangming, MENG Weibo, et al. Specific emitter identification for satellite communication using probabilistic neural networks[J]. International Journal of Satellite Communications and Networking, 2019, 37(3): 283–291. doi: 10.1002/sat.1286 |

| [96] |

ROY D, MUKHERJEE T, CHATTERJEE M, et al. RFAL: Adversarial learning for RF transmitter identification and classification[J]. IEEE Transactions on Cognitive Communications and Networking, 2020, 6(2): 783–801. doi: 10.1109/TCCN.2019.2948919 |

| [97] |

XIE Feiyi, WEN Hong, WU Jinsong, et al. Data augmentation for radio frequency fingerprinting via pseudo-random integration[J]. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence, 2019, . doi: 10.1109/TETCI.2019.2907740 |

| [98] |

MERCHANT K, REVAY S, STANTCHEV G, et al. Deep learning for RF device fingerprinting in cognitive communication networks[J]. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Signal Processing, 2018, 12(1): 160–167. doi: 10.1109/JSTSP.2018.2796446 |

| [99] |

程旗, 赵浩然. 一种基于决策树的信号分类方法[J]. 电子世界, 2018, (13): 28–29, 32.

CHENG Qi and ZHAO Haoran. A signal classification method based on decision tree[J]. Electronics World, 2018, (13): 28–29, 32.

|

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript Peer Review

Peer Review Editor Work

Editor Work

DownLoad:

DownLoad: