| [1] |

方震, 简璞, 张浩, 等. 基于FMCW雷达的非接触式医疗健康监测技术综述[J]. 雷达学报, 2022, 11(3): 499–516. doi: 10.12000/JR22019. FANG Zhen, JIAN Pu, ZHANG Hao, et al. Review of noncontact medical and health monitoring technologies based on FMCW radar[J]. Journal of Radars, 2022, 11(3): 499–516. doi: 10.12000/JR22019. |

| [2] |

HUFF A, KARLEN-AMARANTE M, PITTS T, et al. Optogenetic stimulation of pre-Bötzinger complex reveals novel circuit interactions in swallowing-breathing coordination[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2022, 119(29): e2121095119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2121095119. |

| [3] |

MEHRA R, CHUNG M K, OLSHANSKY B, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiac arrhythmias in adults: Mechanistic insights and clinical implications: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association[J]. Circulation, 2022, 146(9): e119–e136. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001082. |

| [4] |

VAN RUITEN C C, SMITS M M, KOK M D, et al. Mechanisms underlying the blood pressure lowering effects of dapagliflozin, exenatide, and their combination in people with type 2 diabetes: A secondary analysis of a randomized trial[J]. Cardiovascular Diabetology, 2022, 21(1): 63. doi: 10.1186/S12933-022-01492-X. |

| [5] |

LIN Yunan, NOBLE E, LOH C H, et al. Respiration monitoring using a motion tape chest band and portable wireless sensing node[J]. Journal of Commercial Biotechnology, 2022, 27(1). doi: 10.5912/jcb1026. |

| [6] |

LI Chengyu, XU Zijie, XU Shuxing, et al. Miniaturized retractable thin-film sensor for wearable multifunctional respiratory monitoring[J]. Nano Research, 2023, 16(9): 11846–11854. doi: 10.1007/s12274-023-5420-1. |

| [7] |

MOLINARO N, SCHENA E, SILVESTRI S, et al. Multi-roi spectral approach for the continuous remote cardio-respiratory monitoring from mobile device built-in cameras[J]. Sensors, 2022, 22(7): 2539. doi: 10.3390/s22072539. |

| [8] |

WANG Haowen, HUANG Jia, WANG Guowei, et al. Surveillance camera-based cardio-respiratory monitoring for critical patients in icu[C]. 2022 IEEE-EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Ioannina, Greece, 2022: 1–4. doi: 10.1109/BHI56158.2022.9926954. |

| [9] |

LIM C, KIM J, KIM J, et al. Estimation of respiratory rate in various environments using microphones embedded in face masks[J]. The Journal of Supercomputing, 2022, 78(17): 19228–19245. doi: 10.1007/s11227-022-04622-0. |

| [10] |

GONG Hanqin, ZHANG Dongheng, CHEN Jinbo, et al. Enabling orientation-free mmwave-based vital sign sensing with multi-domain signal analysis[C]. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Seoul, Korea, 2024: 8751–8755. doi: 10.1109/ICASSP48485.2024.10448323. |

| [11] |

ZHAI Qian, HAN Xiangyu, HAN Yi, et al. A contactless on-bed radar system for human respiration monitoring[J]. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 2022, 71: 4004210. doi: 10.1109/TIM.2022.3164145. |

| [12] |

KREJ M, BARAN P, and DZIUDA Ł. Detection of respiratory rate using a classifier of waves in the signal from a FBG-based vital signs sensor[J]. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 2019, 177: 31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2019.05.014. |

| [13] |

JANUSZ M, ROUDJANE M, MANTOVANI D, et al. Detecting respiratory rate using flexible multimaterial fiber electrodes designed for a wearable garment[J]. IEEE Sensors Journal, 2022, 22(13): 13552–13561. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2022.3175645. |

| [14] |

XIE Xuecheng, ZHANG Dongheng, LI Yadong, et al. Robust WiFi respiration sensing in the presence of interfering individual[J]. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2024, 23(8): 8447–8462. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2023.3348879. |

| [15] |

ZHANG Binbin, ZHANG Dongheng, LI Yadong, et al. Unsupervised domain adaptation for RF-based gesture recognition[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2023, 10(23): 21026–21038. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3284496. |

| [16] |

HE Ying, CHEN Yan, HU Yang, et al. WiFi vision: Sensing, recognition, and detection with commodity MIMO-OFDM WiFi[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2020, 7(9): 8296–8317. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.2989426. |

| [17] |

WANG Xuyu, YANG Chao, and MAO Shiwen. PhaseBeat: Exploiting CSI phase data for vital sign monitoring with commodity WiFi devices[C]. 2017 IEEE 37th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS), Atlanta, USA, 2017: 1230–1239. doi: 10.1109/ICDCS.2017.206. |

| [18] |

ZHANG Dongheng, HU Yang, CHEN Yan, et al. BreathTrack: Tracking indoor human breath status via commodity WiFi[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2019, 6(2): 3899–3911. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2019.2893330. |

| [19] |

WANG W H, ZENG Xaolu, WANG Beibei, et al. Improved wifi-based respiration tracking via contrast enhancement[C]. IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 2023: 1–2. doi: 10.1109/ICASSP49357.2023.10094823. |

| [20] |

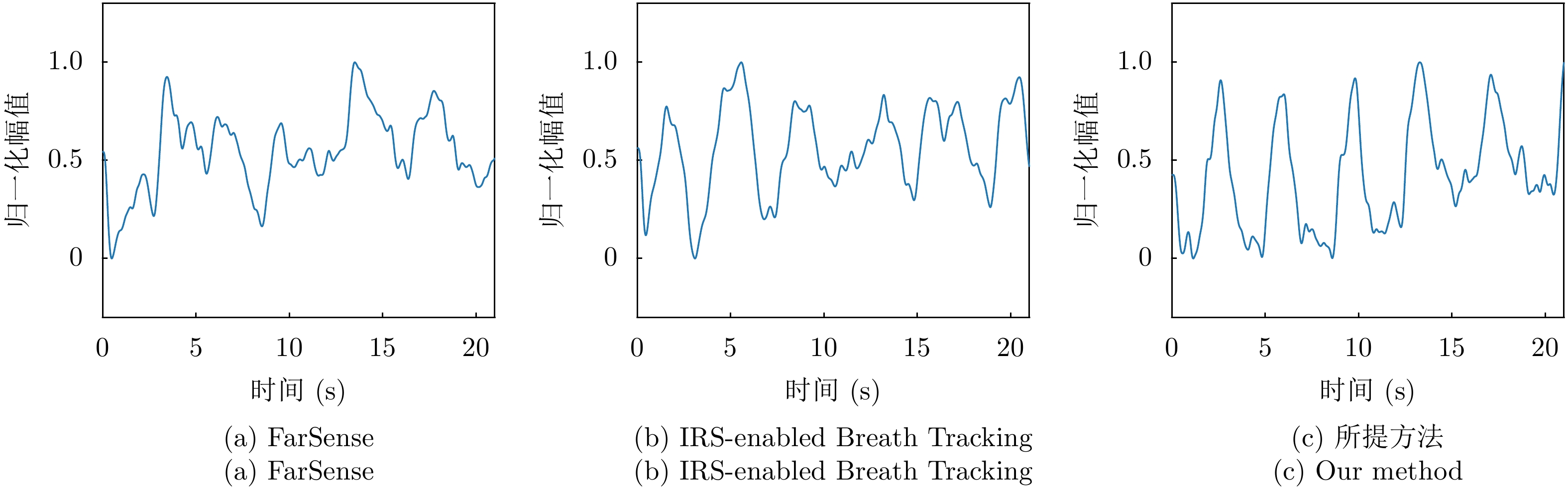

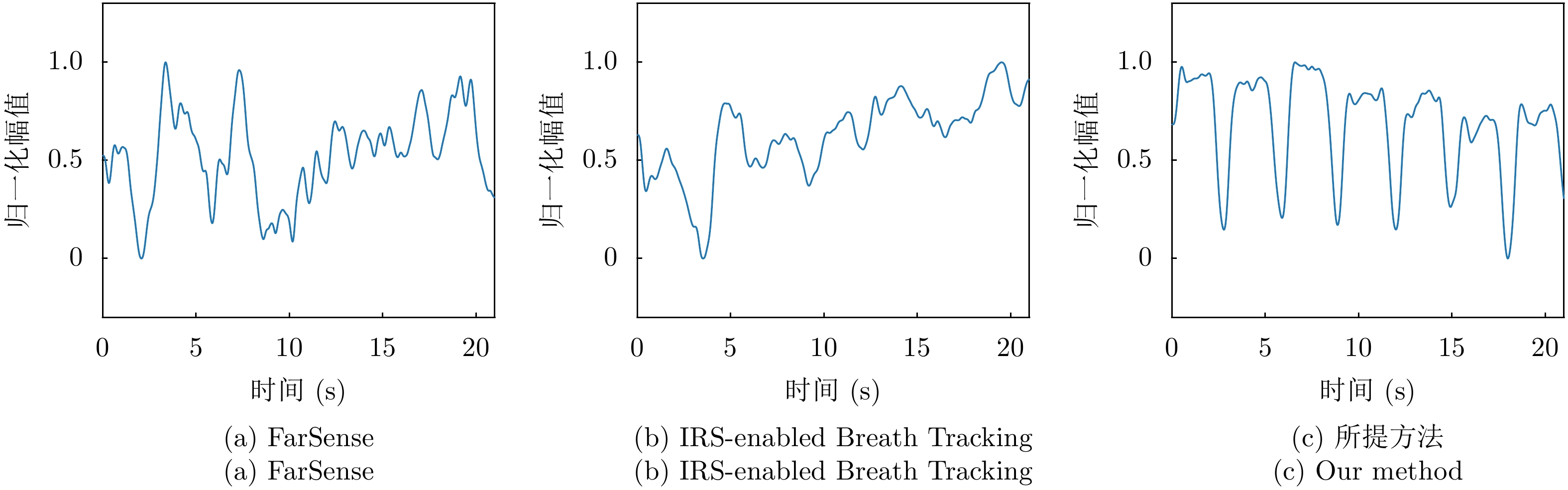

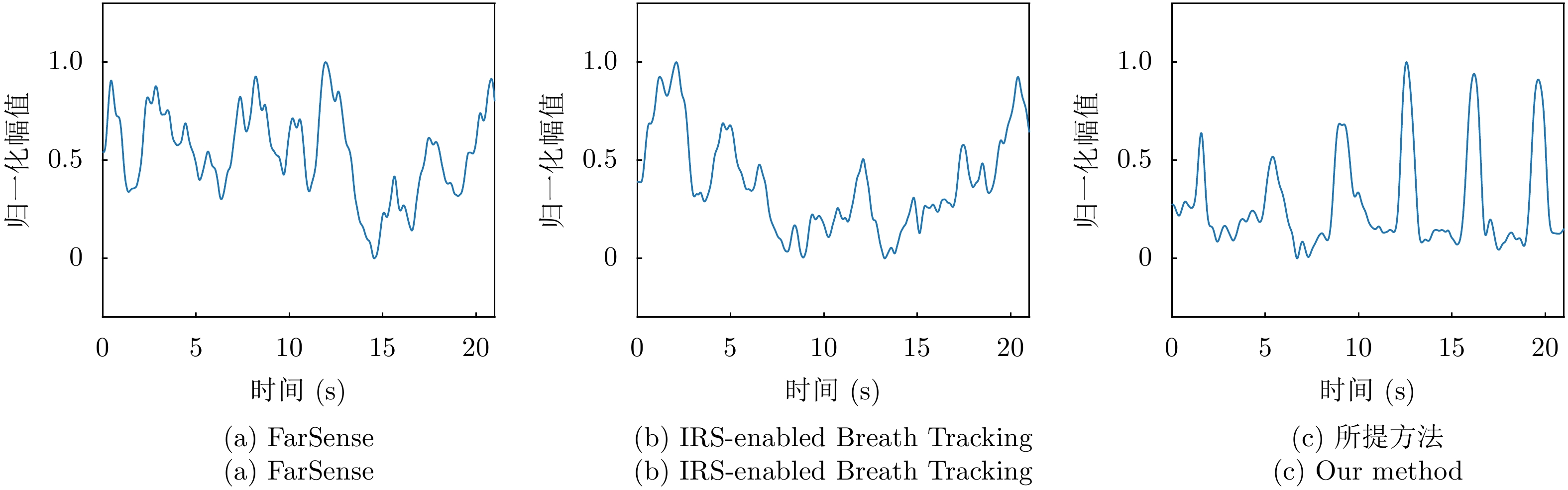

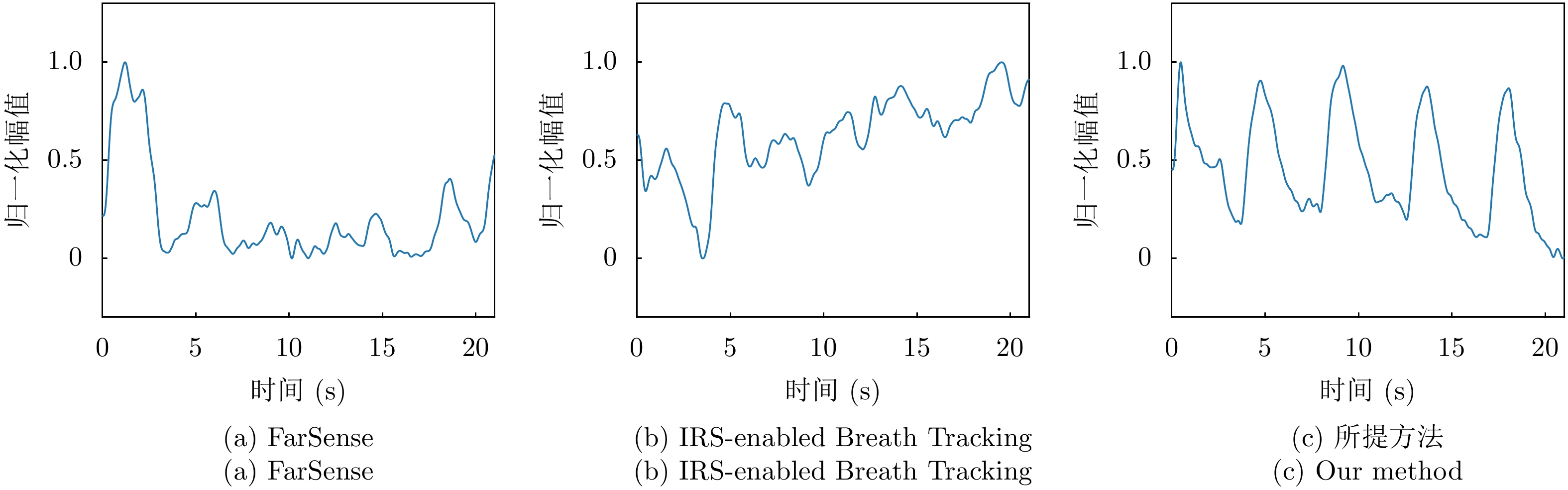

ZENG Youwei, WU Dan, XIONG Jie, et al. FarSense: Pushing the range limit of WiFi-based respiration sensing with CSI ratio of two antennas[J]. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2019, 3(3): 121. doi: 10.1145/3351279. |

| [21] |

LI Lianlin and CUI Tiejun. Recent progress in intelligent electromagnetic sensing[J]. Journal of Radars, 2021, 10(2): 183–190. doi: 10.12000/JR21049. |

| [22] |

ZHANG Ganlin, ZHANG Dongheng, HE Ying, et al. Multi-person passive WiFi indoor localization with intelligent reflecting surface[J]. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, 2023, 22(10): 6534–6546. doi: 10.1109/TWC.2023.3244369. |

| [23] |

田团伟, 邓浩, 鲁建华, 等. 智能反射面辅助雷达通信双功能系统的多载波波形优化方法[J]. 雷达学报, 2022, 11(2): 240–254. doi: 10.12000/JR21138. TIAN Tuanwei, DENG Hao, LU Jianhua, et al. Multicarrier waveform optimization method for an intelligent reflecting surface-assisted dual-function radar-communication system[J]. Journal of Radars, 2022, 11(2): 240–254. doi: 10.12000/JR21138. |

| [24] |

ZHANG Lei, CHEN Xiaoqing, LIU Shuo, et al. Space-time-coding digital metasurfaces[J]. Nature Communications, 2018, 9(1): 4334. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06802-0. |

| [25] |

HE Ying, ZHANG Dongheng, and CHEN Yan. High-resolution wifi imaging with reconfigurable intelligent surfaces[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2023, 10(2): 1775–1786. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2022.3210686. |

| [26] |

蒋卫祥, 田翰闱, 宋超, 等. 数字编码超表面: 迈向电磁功能的可编程与智能调控[J]. 雷达学报, 2022, 11(6): 1003–1019. doi: 10.12000/JR22167. JIANG Weixiang, TIAN Hanwei, SONG Chao, et al. Digital coding metasurfaces: Toward programmable and smart manipulations of electromagnetic functions[J]. Journal of Radars, 2022, 11(6): 1003–1019. doi: 10.12000/JR22167. |

| [27] |

XIA Dexiao, GUAN Lei, LIU Haixia, et al. MetaBreath: Multitarget respiration detection based on space-time-coding digital metasurface[J]. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques, 2024, 72(2): 1433–1443. doi: 10.1109/TMTT.2023.3297413. |

| [28] |

LI Zhi, JIN Tian, GUAN Dongfang, et al. MetaPhys: Contactless physiological sensing of multiple subjects using RIS-based 4-D radar[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2023, 10(14): 12616–12626. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2023.3252587. |

| [29] |

TEWES S, HEINRICHS M, KRONBERGER R, et al. IRS-enabled breath tracking with colocated commodity WiFi transceivers[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2023, 10(8): 6870–6886. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2022.3228158. |

| [30] |

ZHANG Dongheng, HU Yang, CHEN Yan, et al. Calibrating phase offsets for commodity WiFi[J]. IEEE Systems Journal, 2020, 14(1): 661–664. doi: 10.1109/JSYST.2019.2904714. |

| [31] |

CHEN Yan, SU Xiang, HU Yang, et al. Residual carrier frequency offset estimation and compensation for commodity WiFi[J]. IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, 2020, 19(12): 2891–2902. doi: 10.1109/TMC.2019.2934106. |

| [32] |

CHEN Yan, DENG Hongyu, ZHANG Dongheng, et al. SpeedNet: Indoor speed estimation with radio signals[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2021, 8(4): 2762–2774. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2020.3022071. |

| [33] |

HAN Yi, CHEN Yan, WANG Beibei, et al. Enabling heterogeneous connectivity in internet of things: A time-reversal approach[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2016, 3(6): 1036–1047. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2016.2548659. |

| [34] |

XU Qinyi, CHEN Yan, WANG Beibei, et al. TRIEDS: Wireless events detection through the wall[J]. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2017, 4(3): 723–735. doi: 10.1109/JIOT.2017.2663318. |

| [35] |

ZHANG Tianyu, ZHANG Dongheng, WANG Guanzhong, et al. RLoc: Towards robust indoor localization by quantifying uncertainty[J]. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2023, 7(4): 200. doi: 10.1145/3631437. |

| [36] |

REA M, FAKHREDDINE A, GIUSTINIANO D, et al. Filtering noisy 802.11 time-of-flight ranging measurements from commoditized wifi radios[J]. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking, 2017, 25(4): 2514–2527. doi: 10.1109/TNET.2017.2700430. |

| [37] |

XIE Yaxiong, XIONG Jie, LI Mo, et al. mD-track: Leveraging multi-dimensionality for passive indoor Wi-Fi tracking[C]. The 25th Annual International Conference on Mobile Computing and Networking, Los Cabos, Mexico, 2019: 8. doi: 10.1145/3300061.3300133. |

| [38] |

YUE Shichao, HE Hao, WANG Hao, et al. Extracting multi-person respiration from entangled RF signals[J]. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2018, 2(2): 86. doi: 10.1145/3214289. |

Submit Manuscript

Submit Manuscript Peer Review

Peer Review Editor Work

Editor Work

DownLoad:

DownLoad: